Core Skill

Phonological awareness is the broad, umbrella term for the ability to recognize and manipulate the sound structures of spoken language. It includes skills such as syllable awareness and rhyming.

Phonemic awareness is a more specific subset of phonological awareness that focuses on individual phonemes (speech sounds) in spoken words. It includes skills like blending, segmenting, deleting, and substituting phonemes. Phonemic awareness is a critical foundation for learning to read and spell.

Expanded Definition

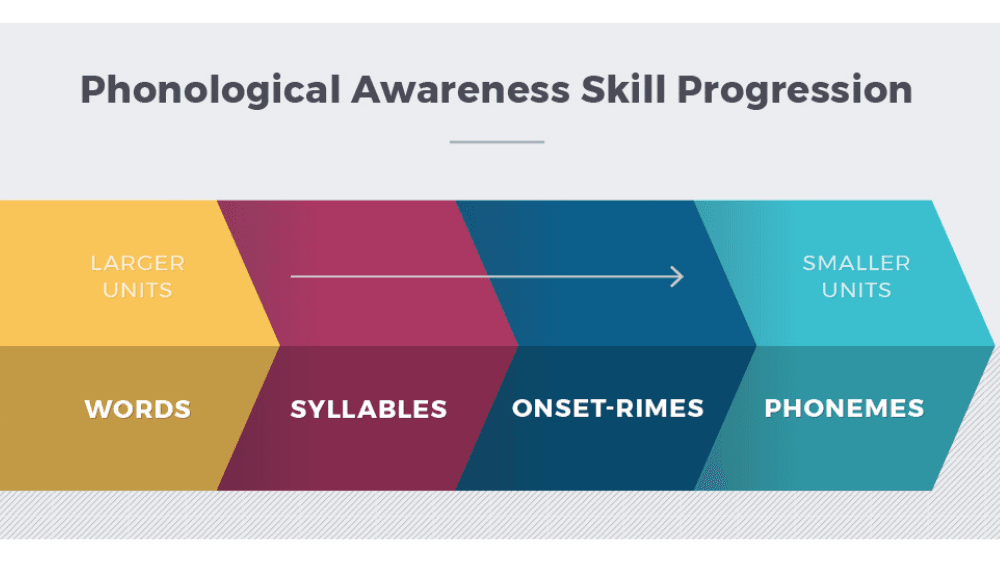

Phonological awareness is a broad category that includes an awareness of larger sound units, such as understanding how sentences are composed of words and words are composed of syllables, as well as smaller units of sounds, such as individual phonemes. These skills are entirely auditory and can be practiced without using letters at all; instead, they focus on a student's ability to attend to and work with the sounds they hear. For example, children with strong phonological awareness can clap out syllables in words, identify rhyming words, and segment the onset and rime in words like cat (/k/ and /ăt). These abilities form the foundation for more advanced sound-level work and support early reading and spelling development.

Phonemic awareness is a more specific subset of phonological awareness and refers to the ability to isolate, discriminate, blend, segment, and manipulate the smallest units of sound in spoken words, called phonemes. Of these, research shows that blending and segmenting most directly relate to literacy development. For example, a child is demonstrating phonemic awareness when she segments the word ship into its individual sounds /sh/ /ĭ/ /p/ in order to spell it. These skills are essential because they serve as a bridge between spoken language and written language through phonics instruction. Once a student can identify the sounds that the letters <d>, <o>, and <g> represent, they subsequently need to be able to blend the three corresponding phonemes together before they have successfully read the word. Similarly, a student must first segment a word into individual phonemes before writing the corresponding letters for each sound when spelling.

It is important to note that while these skills can be practiced without printed letters or words, they should not always be. While young students engaging in phonological awareness word play may not have the written words in front of them, as soon as students have learned letter-sound correspondences, these letters should be used in phonemic awareness practice.

The Research

Research supports the necessity of phonemic awareness skills for both students' reading and spelling development. Numerous studies have shown that struggling readers are likely to demonstrate poor phonemic awareness skills (Adams, 1990; Stanovich, 1986). In fact, deficits in phonemic awareness are a hallmark of early reading difficulties, including dyslexia. Because students should be able to demonstrate these phonemic awareness skills before they even learn sound-letter correspondences (Hulme et al., 2005), difficulty with these activities in Kindergarten and 1st grade can also be a strong predictor of future reading struggles (Hogan et al., 2005).

These phonemic-level skills develop as part of a larger continuum of phonological awareness skills, which include the ability to manipulate larger sound units such as syllables, rhymes, and onsets and rimes. Research suggests that while instruction in broader phonological skills can be helpful, it is explicit, systematic instruction in phoneme-level tasks—particularly blending and segmenting—that most directly supports decoding and early word reading (National Reading Panel, 2000).

Luckily, teachers can provide effective instruction in phonemic awareness skills through modeling and guided practice, whether as a whole-class activity or in small groups as needed (Al Otaiba et al., 2016; Ouellette & Sénéchal, 2008). Studies have shown that these skills can be taught successfully in whole-class settings, small groups, or through targeted intervention, making phonemic awareness instruction a powerful and flexible tool for early literacy support.

Take Note: Additional Considerations for Targeting this Skill

1. Blend first, then segment. Blending (whether with syllables or sounds) is usually an easier task for children than segmenting.

2. Phonemic awareness is a necessary literacy skill. Unlike phonological awareness activities targeting larger units of language (such as rhyming words), the ability to blend and segment words at the phoneme level is necessary for proficient literacy development, and teachers should continue to target the skill with struggling readers and spellers, regardless of age/grade.

3. Keep it short. Phonological and phonemic awareness activities should be short. Most students will benefit from 5-10 minutes per day.

Differentiation

- The use of picture cues can help reinforce or introduce new vocabulary. This can be especially helpful for English Learners and students with language difficulties.

- Consider that even simple CVC words can provide opportunities for vocabulary enrichment by selecting potentially unfamiliar words (sob, sap, dim, mash, fib) and/or words that have multiple meanings (run, ram, tip, lap, bug).

- Words that use phonemes absent from a student's native language or dialect can be especially difficult for them to accurately isolate, produce, or discriminate from other similar-sounding phonemes. Provide additional instruction and practice opportunities as needed.

Adams, M.J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Al Otaiba, S., McMaster, K., Wanzek, J., & Zaru, M. W. (2023). What We Know and Need to Know about Literacy Interventions for Elementary Students with Reading Difficulties and Disabilities, including Dyslexia. Reading research quarterly, 58(2), 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.458

Hogan, T. P., Catts, H. W., & Little, T. D. (2005). The relationship between phonological awareness and reading: implications for the assessment of phonological awareness. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 36(4), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2005/029)

Hulme, C., Snowling, M., Caravolas, M., & Carroll, J. (2005). Phonological Skills are (Probably) One Cause of Success in Learning to Read: A Comment on Castles and Coltheart. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0904_2

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Ouellette, G. P., & Sénéchal, M. (2008). A window into early literacy: Exploring the cognitive and linguistic underpinnings of invented spelling. _Scientific Studies of Reading, 1_2(2), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430801917324

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022057409189001-204