Core Skill

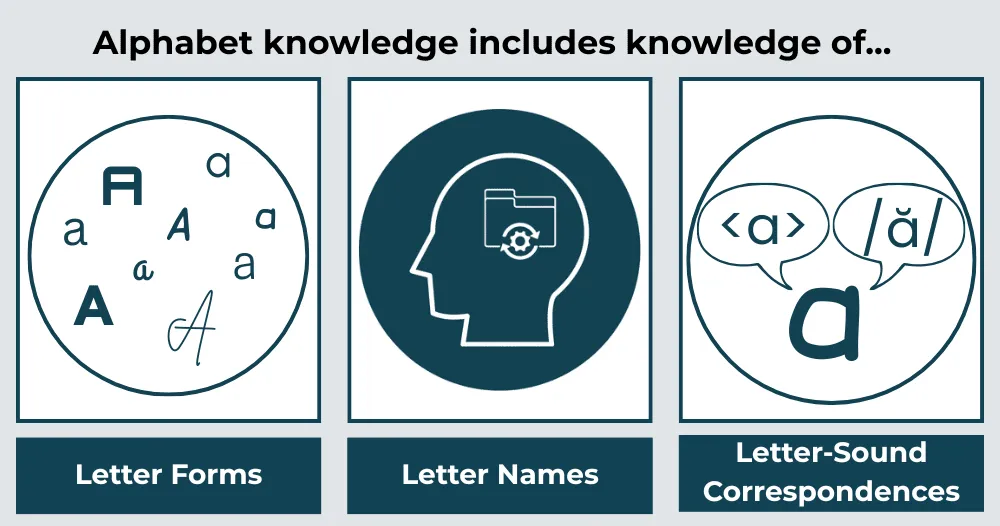

Alphabet knowledge includes knowledge of letter forms, letter names, and letter-sound correspondences. These early literacy skills are highly predictive of later literacy development.

Expanded Definition

Letter form knowledge- the ability to identify and distinguish one letter from another despite variations in form (e.g., different fonts or handwriting styles) and reproduce letters.

Letter name knowledge- the ability to give a name or label to a letter. This can be thought of as the “file folder” under which a student can store all the learned characteristics of a letter. It is beneficial to know because a letter’s name remains the same while a letter’s form and sound can vary.

Letter-sound correspondence knowledge- the ability to pair a letter with its most common corresponding sound enables learners to begin to apply the alphabetic principle (the understanding that written letters represent spoken sounds).

Research has consistently shown that strong alphabet knowledge is a well-established early predictor of later reading success. Conversely, difficulty learning letter names and sounds is a key early indicator of future reading challenges. Yet, evidence also shows that targeted instruction helps develop these skills. Developing automaticity in the components of alphabet knowledge lays the groundwork for understanding our alphabetic system. This, in turn, supports fluent reading, spelling, and overall literacy development.

The Research

Alphabet knowledge is a critical skill for literacy development in an alphabetic language and is consistently a strong early predictor of later word reading abilities (Demchak & Solari, 2025; NELP, 2008). Children with limited letter knowledge in preschool and kindergarten are at greater risk for reading difficulties (NELP, 2008; NCECDTL, 2020), making early targeted instruction essential. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-led instruction that integrates letter names, sounds, and writing within a structured and logical sequence is most effective (Demchak & Solari, 2025; Lonigan et al., 2013; Piasta & Wagner, 2010). Learning letter names may aid letter-sound acquisition, and letter sounds are essential for decoding and encoding. Therefore, an approach in which letter names and sounds are taught together is typically most efficient. The National Reading Panel (2000) and subsequent research, including those by Piasta and Wagner (2010) and Lonigan et al. (2013), have also found that incorporating direct alphabet instruction alongside phonological awareness activities results in the most significant gains. Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of delivering alphabet instruction early and systematically to lay the foundation for proficient reading and writing.

Take Note: Additional Considerations for Targeting this Skill

- Not a letter a week. Given the number of letters students need to learn, introducing one letter per week is too slow. Some letters are easier to learn than others, making uniform pacing ineffective (see "Consider the characteristics..." below). Using an approach that introduces some letters or groups of letters more rapidly will provide more cycles for repeated practice and review, and may be more effective.

- Consider the characteristics of letters. Students typically learn letters in their name more quickly, as well as those at the very beginning of the alphabet and letters whose names closely align with their sounds (e.g., the letter name <t> starts with the /t/ sound, whereas the letter name <w> does not use the /w/ sound at all).

- Draw students' attention to the salient letter features. The type of letter tiles and cards used for alphabet knowledge activities matters less than ensuring students recognize letters by their form, not extraneous details. For example, students shouldn't identify <a> because the tile is green, because the <a> letter card is folded down in the corner, or because there is an apple on the card, but instead because <a> has a circle and short line on the right.

- Avoid teaching visually similar letters all at once. For example, do not group the letters <b>, <d>, <p>, and <q> for initial introduction.

- Use precision with sounds. Make sure that you and your students are articulating only the targeted, individual sound, such as /b/, and not adding a vowel sound after (such as 'buh'). This is sometimes referred to as clipping your sound.

- Use precision with terminology. Students must understand the difference between a letter name and a letter sound. When you ask for a letter name, expect a letter name. When you ask for a letter sound, expect a letter sound.

- Maintain a brisk, supportive pace. Keep activities moving to maintain engagement and increase practice opportunities. When students make an error, pause briefly to model the correct response and allow the group to repeat. Avoid lingering too long on any single item to preserve momentum.

- Connect alphabet knowledge to decoding early. Isolated letter-sound instruction is less effective than instruction that integrates letter learning with phonemic awareness and phonics activities. Once students recognize a few letter-sound correspondences, introduce blending to read simple words.

Differentiation

- For students with memory challenges, prioritize learning high-utility letters. These letters should be chosen to maximize early reading opportunities, allowing students to apply their knowledge to decoding as soon as possible. For example, learning the correspondence for <t> will allow them access to more words than <w>.

- Embedded letter mnemonics (such as AIM's Animated Alphabet) can help beginning readers, struggling readers, and students with memory challenges as a temporary scaffold to help learners connect letters to their corresponding sounds. It uses a visual representation of an object that begins with the letter's sound, embedded into the letter shape itself. For example, the letter <s> is designed to look like a snake. Embedding the image in the letter rather than under the letter helps to draw students’ attention to the letter’s form.

- When possible, familiarize yourself with the phonemic systems in the languages your students speak. When an English phoneme does not exist in a student's native language, provide additional instruction and practice to reinforce the letter-sound relationship.

- For English Learners who have received literacy instruction in their native language, consider the differences in letter-sound relationships between their language and English as appropriate. In alphabetic languages, some letters may overlap with English but have different names and/or sounds. For example, the letter <i> in Spanish is named and pronounced like the long /ē/ sound in English. When a letter-sound relationship differs from its English correspondence or the letter does not exist in a student's native written language, provide additional instruction and practice to reinforce the letter-sound relationship.

Demchak, A., & Solari, E. (2025). Brick by brick: Insights on alphabet instruction. The Reading League Journal, 6(1), 21-26.

Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188.

Lonigan, C. J., Purpura, D. J., Wilson, S. B., Walker, P. M., & Clancy-Menchetti, J. (2013). Evaluating the components of an emergent literacy intervention for preschool children at risk for reading difficulties. Journal Experimental Child Psychology, 114(1),111-130.

National Center on Early Childhood Development, Teaching, and Learning. (2020). Interactive Head Start early learning framework: Ages birth to five. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://headstart.gov/interactive-head-start-early-learning-outcomes-framework-ages-birth-five

National Early Literacy Panel. (2008). Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. National Center for Family Literacy. Retrieved from https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/NELPReport09.pdf

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Piasta, S. B., & Wagner, R.K. (2010). Learning letter names and sounds: Effects of instruction, letter type, and phonological processing skill. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 105(4), 324-344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2009.12.008

Piasta, S.B., & Wagner, R.K. (2010) Developing early literacy skills: A meta-analysis of alphabet learning and instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(1), 8-38. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.45.1.2

Sunde, K., Furnes, B., & Lundetræ, K. (2019). Does introducing the letters faster boost the development of children’s letter knowledge, word reading, and spelling in the first year of school? Scientific Studies of Reading, 24(2), 141-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2019.1615491