Core Skill

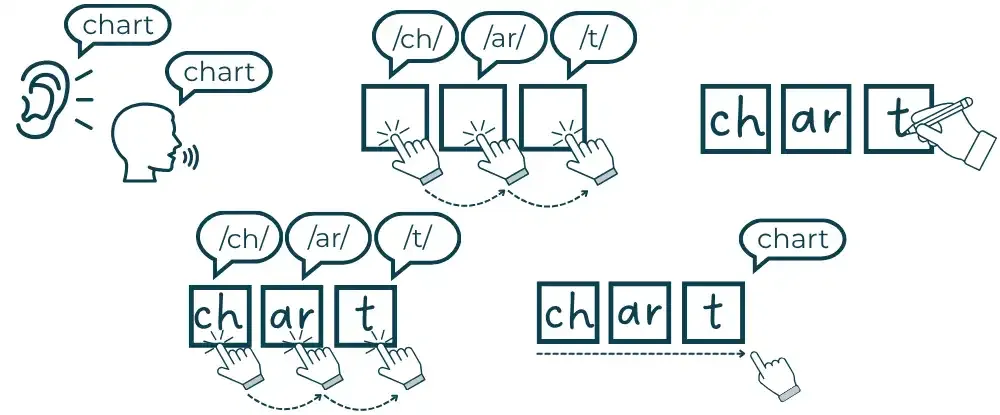

Encoding is the process of taking a spoken word, segmenting it into smaller parts, and representing those parts in written form. It is the reverse process of decoding and a component of spelling.

Spelling is often used synonymously with encoding, but spelling refers to a broader linguistic process. While some words can be spelled using encoding alone, others require writers to apply spelling conventions unique to each written language system.

Expanded Definition

To learn to read and spell, students must develop an understanding of the alphabetic principle—the insight that letters systematically and predictably correspond to spoken sounds. Systematic phonics instruction is one of the most effective ways to develop this knowledge, especially for beginning and struggling readers. Systematic phonics instruction explicitly teaches students a planned, sequential set of relationships between graphemes (letters) and phonemes (sounds). This understanding then lays the foundation for more advanced instruction in how meaning and sound interact in English words. Students apply their phonics knowledge when they decode and encode. Decoding and encoding skills have a reciprocal relationship, meaning instruction in one often contributes to growth in the other.

At the early stages of spelling, many basic words (e.g., hop, just, slump) can be spelled correctly using encoding alone. As described above, to encode a word, students must segment it into phonemes and retrieve the corresponding graphemes. However, just because a student can read a word doesn’t mean they can spell it. One reason for this is that writing a word requires students to produce a full string of letters in an accurate order, rather than recognizing the letter string. Producing this information is more challenging than recognizing. Additionally, English spelling requires what researchers refer to as orthographic knowledge. Apel (2011) defines orthographic knowledge as “stored information in memory for the correct way to write a language’s orthography” (p. 595).

Because English phonemes are represented by more than one grapheme, sometimes generalizations can be learned to support spelling decisions. For example, the phoneme’s placement in the initial, medial, or final position within a syllable can sometimes determine which grapheme is used. Knowing the phoneme /ā/ is in the final position and typically spelled <ay> helps writers spell bay correctly, and not bai. However, there isn’t always such a pattern to fall back on. Neither bear nor bare is spelled ‘bair’ simply because ‘bair’ is not an English word. So, while word reading and spelling are highly correlated, as words become more complex, a student’s ability to decode often outpaces their spelling ability. For some words, repeated exposure and attention to a word’s spelling are needed to develop the precise knowledge necessary to spell the word correctly.

In many words, knowledge of the word’s morphemes (meaningful word parts) may also impact spelling. Students need to understand how morphemes, and sometimes the origins of these morphemes, influence letter choice. For example, for students to know that the last /t/ sound in jumped should be spelled with <ed> and not <t>, they need to recognize that the word contains a suffix that indicates the action happened in the past.

The Research

Ehri (2000) explains that reading and spelling are two sides of the same coin, sharing overlapping cognitive processes and similar underlying knowledge. Fundamentally, both require students to connect their language system to a writing system. Because systematic phonics instruction teaches phoneme-grapheme correspondences, it is essential for establishing this connection, particularly in the early grades (National Reading Panel, 2000). Due to the overlap in processes, strong readers tend to be relatively strong spellers, and vice versa (Kim, et al., 2024; Treiman et al., 2025). For these reasons, phonics instruction must integrate decoding, encoding, and spelling to help students transfer knowledge between word reading and word spelling.

As with decoding, spelling instruction should progress from simple to complex. This means initially, instruction may prioritize equipping students with strategies to encode words using segmentation skills and phonics knowledge to generate spellings independently, rather than always providing the word’s spelling for them to copy. This may result in spelling approximations, sometimes referred to as inventive spelling (Graham et al., 2012). This practice strengthens phonemic segmentation, which is a strong predictor of spelling skills (Nation & Hulme, 1997).

However, because many English words can not be spelled using phonics alone, formal spelling instruction (beyond encoding) is necessary for students to learn conventional spelling (Alves et al., 2019). Explicit spelling instruction typically includes direct practice spelling individual words, instruction on applying spelling generalizations to spell unknown words (e.g., words in English don’t with <j> or <v>), and a broader analysis of spellings through word study. When compared to incidental instruction, where spelling mistakes are caught and taught as they come up, formal spelling instruction leads to lasting gains not only in spelling but also in phonological awareness, reading, and writing. Generally, more instruction results in stronger effects, although the optimal instructional time remains unclear (Graham & Santangelo, 2014).

Crucially, students do not need to have mastered spelling accuracy before transferring these skills to writing. Students can simultaneously develop writing composition skills, even with limited spelling accuracy. As basic writing skills, including spelling, become relatively effortless, writers can shift their focus to developing and communicating ideas (Graham et al., 2012). When this happens, writers tend to write more, which helps them feel more confident and view themselves as better writers (Berninger et al., 2002). Therefore, one goal of spelling instruction is to help students develop automaticity. In sum, teaching spelling explicitly, systematically, and in connection with both decoding and writing is an instructional priority even with modern spell check and text-to-speech tools. This instruction helps build the foundational skills necessary for reading and writing.

Take Note: Additional Considerations for Targeting this Skill

- Prioritize newly taught phonics patterns in practice. A helpful target is approximately 80% of practice devoted to new or unmastered grapheme-phoneme correspondences, with the remaining 20% focused on cumulative review. Provide multiple opportunities to encode words with the same newly introduced grapheme (e.g., thin, then, math) to promote retention.

- Group words around common spelling patterns. Rather than using word lists that are related by themes (e.g., colors or months of the year), organize instruction around specific phoneme-grapheme correspondences, orthographic patterns (e.g., the doubling of <l> in pull, roll, and full), or morphemes.

- Avoid activities that encourage rote memorization. Activities such as copying words, word searches, or rote memorization rely heavily on visual memory and do not support the skills necessary for proficient encoding. Instead, spelling activities should support students in extracting rules and patterns so that this learning can be generalized to related words.

- Use precision with terminology. Students must understand the difference between a letter name and a letter sound. When you ask for a letter name, expect a letter name. When you ask for a letter sound, expect a letter sound.

Differentiation

- For English Learners who have received literacy instruction in their native language, identify differences in phoneme-grapheme relationships between their language and English. In alphabetic languages, some graphemes may overlap with English but are used to represent different phonemes. When a phoneme-grapheme relationship differs from its English correspondence or a phoneme or grapheme does not exist in a student's native written language, provide additional instruction and practice to reinforce the relationship.

- Words that use phonemes absent from a student's native oral language or dialect can be especially difficult to accurately segment and encode. Provide additional instruction and practice opportunities as needed.

- Embed opportunities to build language. Consider that even simple CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words can provide opportunities for vocabulary enrichment and practice shifting between the multiple meanings that words such as pen and jam can have. The use of picture cues and using words in the context of a sentence can help reinforce or introduce new vocabulary. This can be especially helpful for English Learners and students with language difficulties.

- Students with spelling difficulties, including those with dysgraphia, often benefit from highly explicit instruction, immediate feedback, and ample review. The number of encounters a child needs with a word before being able to spell the word correctly can vary significantly. Provide multiple opportunities to spell words and repeated exposures with difficult patterns to ensure mastery.

- For students with language variations different from Standard American English, consider the strategy of spelling with a “spelling voice.” Many of us use this strategy when spelling a word like Feb-ru-ary. Point out to students that when writing, they may think of an alternate pronunciation to match the letters in the word’s spelling, and that this may be different than when speaking the word. For example, a student in the South may pronounce pen and pin identically. Therefore, when spelling pen, a student may want to segment the sounds as /p/…/ĕ/…/n/. The goal is not to change the way the student says the word. The goal is to honor the students’ oral language system while simultaneously building knowledge of conventional spelling.

- For students who struggle with segmentation, scaffold encoding tasks with concrete tools like Elkonin boxes or syllable lines to support students in segmenting sounds. For additional activities and guidance on instruction in this skill area, review our Phonological/Phonemic Awareness Skill Overview.

Alves, R. A., Limpo, T., Salas, N., & Joshi, R. M. (2019). Handwriting and spelling. In C. A. MacArthur, S., Graham., & M. Hebert (Eds.), Best practices in writing instruction. (3rd ed., pp. 211-233). Guilford Press.

Apel, K. (2011). Tutorial: What is orthographic knowledge? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 592-603.

Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K., Abbott, R. D., Begay, K., Coleman, K. B., Curtin, G., Hawkins, J. M., & Graham, S. (2002). Teaching spelling and composition alone and together: Implications for the simple view of writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 291-304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.291

Ehri, L. C. (2000). Learning to read and learning to spell: Two sides of a coin. Topics in Language Disorders, 20(3), 19-36. https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-200020030-00005

Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Booth Olson, C., D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D., & Olinghouse, N. (2012). Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012- 4058). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/WWC/PracticeGuide/17

Graham, S., & Santangelo, T. (2014). Does spelling instruction make students better spellers, readers, and writers? A meta-analytic review. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27(9), 1703-1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-014-9517-0

Hilte, J., & Reitsma, P. (2006). Spelling pronunciation and visual preview both facilitate learning to spell irregular words. Annals of Dyslexia, 56(2), 301-318.

Kim, Y. S. G., Wolters, A., & Lee, J. W. (2024). Reading and writing relations are not uniform: They differ by the linguistic grain size, developmental phase, and measurement. Review of Educational Research, 94(3), 311-342. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543231178830

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Ocal, T., & Ehri, L. C. (2017). Spelling pronunciations help college students remember how to spell difficult words. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(5), 947-967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-016-9707-z

Treiman, R., Hulslander, J., Willcutt, E. G., Pennington, B. F., & Olson, R. K. (2025). On the relationship between word reading ability and spelling ability. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 38, 1509-1531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10566-z