Core Skill

Vocabulary knowledge exists on a spectrum. We know the meanings of some words, along with their connotations, well. We use these words readily and easily in speech and writing. We recognize other words, but with only a vague understanding of their meanings (It has something to do with computers, I think), or not at all (I've heard that word before, but I don't know what it means). Because of this variability, when we consider vocabulary knowledge, we should account for both vocabulary breadth (how many words one is familiar with) and depth (how well some of those words are known).

Expanded Definition

Although vocabulary is often assessed through tasks like labeling pictures or identifying words by pointing, truly knowing a word involves much more than that. Full understanding and flexible use of a word requires deep, multifaceted knowledge. One helpful framework for thinking about the dimensions of word knowledge is the acronym POSS'M, originally coined by Dr. Maryanne Wolf (2007). It stands for Phonology, Orthography, Semantics, Syntax, and Morphology.

- Phonology refers to how a word is pronounced. For instance, someone who has only encountered the word rapport in print may mispronounce it, not realizing the final <t> is silent.

- Orthography addresses how the word is spelled. For example, while it may be phonologically permissible to spell the sounds /tēm/ as teem or teme, the word only means a group of people working or competing together if spelled team.

- Semantics involves the word’s meaning, including nuances such as multiple meanings (pen as a writing tool or animal enclosure) and connotations (childish vs. childlike).

- Syntax refers to how the word functions in a sentence, including its part of speech and appropriate word order. For example, in English it is most natural to say small blue ball, rather than blue small ball, and certainly not ball small blue.

- Morphology deals with the structure of the word, including its roots and affixes. For example, recognizing the connection between muscle and muscular, or understanding how break can become unbreakable through the addition of prefixes and suffixes.

Some educators and researchers expand POSS'M to include Pragmatics, which captures the social and contextual dimensions of language use. This includes knowing when and with whom certain words are appropriate, such as when using technical jargon or informal slang might be out of place.

The Research

Vocabulary is a vital contributor to reading comprehension. In fact, once accurate and automatic word recognition is in place, vocabulary becomes one of the strongest predictors of how well a text is understood (Stahl & Nagy, 2006). This is especially true as texts become more complex and increasingly reliant on background knowledge and word meaning.

Vocabulary knowledge is an essential skill not only for comprehending a text, but for accurately reading words as well (National Reading Panel, 2000). Because English is written with a deep orthography, not all words have a perfect, one-to-one correspondence with speech sounds. For instance, the vowel team <ea> can represent three different vowel phonemes. Thus, to correctly decode the word break, a student would need to know that neither /brēk/ nor /brĕk/is a real word, but /brāk/ is.

In addition to supporting word reading accuracy, vocabulary knowledge contributes to efficient, automatic word recognition. According to Linnea Ehri’s Theory of Orthographic Mapping, words become permanently stored for automatic retrieval when readers form strong connections between a word’s phonemes (sounds) and graphemes (letters). This process allows the pronunciation, spelling, and meaning of a word to become bonded in memory, enabling rapid recognition (Ehri, 2014). Building on this foundation, Charles Perfetti’s Lexical Quality Hypothesis posits that how well a reader knows a word’s meaning, spelling, and pronunciation determines how efficiently it is recognized and read (Perfetti, 2007).

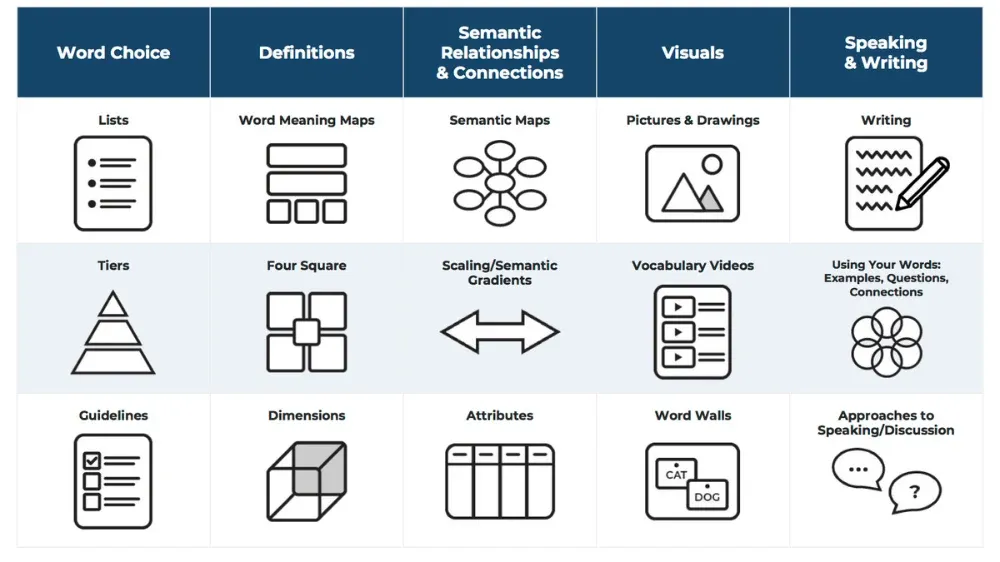

It is important to remember that vocabulary growth happens from both implicit and explicit learning (National Reading Panel, 2000). Most of the words we use regularly were learned implicitly by hearing and reading the word multiple times, in multiple different contexts. This helps us shape and refine our understanding of the word’s usage and meaning(s) (Hirsch, 2003; Stahl, 2003). Some words, however, require explicit learning– a direct explanation of the word’s definition and how it is used (Beck et al., 2002). As educators, we can help foster our students’ vocabulary growth by: providing direct, explicit instruction in high utility words; tapping into their incidental learning by exposing them to sophisticated, academic vocabulary through both oral and written language; providing them with word-learning strategies to access word meanings independently; and promoting an interest and curiosity in understanding and using a rich vocabulary.

Take Note: Additional Considerations for Targeting this Skill

1. Explain useful but high-utility words. Dedicate instructional time to teaching words that students are unlikely to already have a firm grasp of and use independently, but that they will be likely to read again in multiple texts.

2. Explain obscure words quickly. When students encounter an unusual, esoteric word that they are unlikely to come across frequently (sometimes known as Tier III words), explain the word’s meaning quickly so that they can understand the text, and then move on.

3. Engage all modalities. Students will learn the word best when they can hear it and read it, as well as say and write it themselves.

4. Vocabulary is intrinsically linked with background knowledge. Keep in mind that fostering developing skills in one of these key components of reading comprehension will aid in the other.

5. You have to know something to learn something. This saying is appropriate for many ideas, especially vocabulary learning. Word meanings are best cemented when their relationships with other, known words are made clear. For example, if teaching the word glimpse, a teacher would want to explain that it is a type of look that is very quick. It is similar to a glance, but may imply that it was accidental, unlike the word glance. She may continue that its opposite could be a stare.

Differentiation

- Consider that what might be a common, familiar word to you or some students may be novel to others. Generational, cultural, regional, and socio-economic differences can all contribute to the type of words we are exposed to in everyday life. Consider the needs of your students when selecting words to explain and/or provide direct instruction with.

- Non-native English speakers often have difficulty learning idioms, so be sure to include these in your language instruction. As always, focus on ones students are likely to come across in written and oral language today (on the same page; in the long run; up in the air), rather than those that are outdated or irrelevant (raining cats and dogs, paint the town red).

- When teaching words, providing multiple contexts of common usages can be especially helpful for English Learners unfamiliar with typical collocations. For example, while quick and fast mean the same thing, we would only use the latter before the word car.

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction. New York, NY: Guilford Press Book/Childcraft International.

Ehri, L. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 5–21. doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Hirsch Jr., E. D. (2003). Reading Comprehension Requires Knowledge of the Words and the World: Scientific Insights into the Fourth-Grade-Slump and the Nation’s Stagnant Comprehension Scores. American Educator, 27, 10-29.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Perfetti, C. A., & Hart, L. (2001). The lexical basis of comprehension skill. In D. S. Gorfein (Ed.), On the consequences of meaning selection: Perspectives on resolving lexical ambiguity. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10459-004

Stahl, S. A. (2003). Vocabulary and readability: How knowing word meanings affects comprehension. Topics in Language Disorders, 23(3), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-200307000-00009

Stahl, S. A., & Nagy, W. E. (2006). Teaching word meanings. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Wolf, M. (2007). Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. HarperCollins.