Core Skill

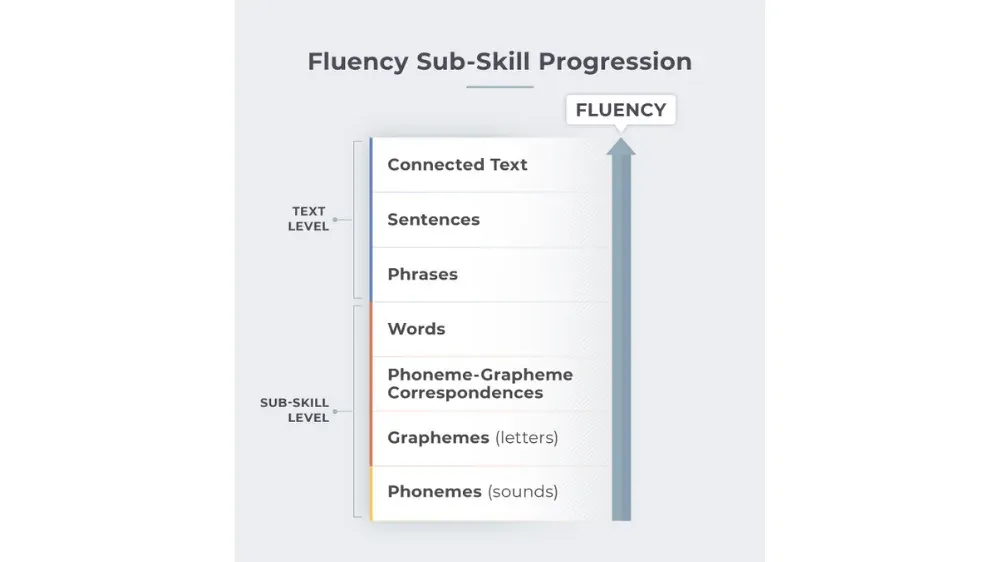

Automaticity is the ability to implement a skill not only accurately, but with quick, effortless retrieval. Automaticity with foundational reading subskills is a necessary step in the progression of building reading fluency.

Fluency is the ability to read connected text with accuracy, automaticity, and proper expression.

Expanded Definition

While automaticity and fluency are highly related terms, they are not exactly synonymous. Automaticity refers to the quick, effortless retrieval of knowledge or execution of a skill. In reading, it suggests that proficient readers not only recognize familiar words quickly and easily but do so involuntarily. For example, the Stroop effect demonstrates this phenomenon by showing how difficult it is to suppress automatic word recognition. When asked to name the color of a word’s font (e.g., saying "red" when the word yellow is printed in red), people tend to experience delays and errors because their brain automatically processes the written word before they can focus on its color. Automaticity can be demonstrated at the subskill (e.g., letter-sound correspondences and word reading) and text level (including phrases, sentences, or connected text).

Fluency, on the other hand, is a skill that can only be demonstrated at the text level. It implies not only that the words were read with automaticity, but also with appropriate prosody, or expression. For example, a student may read a text quickly, but ignore the appropriate pauses and intonation needed from the text’s punctuation and phrasing. This would suggest automaticity, but not the goal of fluency, which is what supports comprehension.

When considering how to reach fluency with connected text, students should first be expected to demonstrate automaticity with subskills.

The Research

Fluency and comprehension share a reciprocal relationship, where improvements in one skill reinforce the other. For beginning readers, encountering unfamiliar words is common, making efficient decoding essential for maintaining fluency (Hudson et al., 2009). The importance of these subskills does not subside as reading proficiency increases, however. Leading theories suggest that effortless sight word recognition relies on foundational subskills like alphabetic knowledge and letter-sound correspondences (Ehri, 1992), which are likely strengthened through consistent practice (Rayner et al., 2001). The ability to read words quickly and effortlessly ensures that cognitive resources can be directed toward higher-order processes, such as comprehending the text’s meaning rather than struggling with individual words (Perfetti, 1985). However, while this theoretical framework supports the importance of developing automaticity in reading subskills, there is limited empirical evidence showing that training focused on building subskill automaticity directly improves oral reading fluency and comprehension (the intended outcome). A recent meta-analysis has shown some positive effects of practicing word-reading automaticity, but the effect size was not statistically significant, suggesting that while there may be benefits, the strength of this relationship requires further investigation (Cooper et al., 2022).

Research does, however, consistently support the benefits of fluency instruction using connected texts, showing that it improves not only oral reading rate and accuracy itself, but also reading comprehension (Kuhn & Stahl, 2003; National Reading Panel, 2000). Studies highlight that approaches like Repeated Oral Reading (Kuhn & Stahl, 2003) and modeled fluent reading (Armbruster et al., 2001) help students develop automatic word recognition and prosody, freeing up cognitive resources for understanding text. It is important to understand that while fluency is often measured in terms of rate using measures like words correct per minute (WCPM), it is not a matter of the faster the better. Research suggests diminishing returns to increasing a student’s WCPM beyond the 50th percentile, as compared to other students in their grade level. While fluency gains up to this point are often linked to improved comprehension, further increases in speed (faster than a typical rate of speech in oral language, for example) do not necessarily yield gains in understanding. In fact, rushing through reading in this manner may even decrease a student’s comprehension, underscoring the importance of fluency instruction that also attends to prosody and meaning (Hasbrouck & Glaser, 2018).

Prosody (the rhythm, phrasing, and intonation of oral reading) is often seen as a bridge between accurate word reading and comprehension. Expressive reading that resembles the prosody of oral language reflects a reader’s understanding of sentence structure, punctuation, and meaning (Rasinski, 2012) and is associated with improved comprehension outcomes. In other words, when readers sound like they understand what they’re reading, they often do (Rasinski & Smith, 2018).

Take Note: Additional Considerations for Targeting this Skill

1. Consider authentic texts. For example, poetry is a valuable tool for fluency instruction because its natural rhythm supports the development of prosody. Reading poetry aloud encourages students to attend to pacing, expression, and phrasing in ways that align closely with fluent reading.

2. Use cross-curricular texts. Fluency practice can extend beyond narrative texts to include cross-curricular content. Using science, social studies, and other informational texts for fluency instruction not only supports transfer of fluency skills but also reinforces comprehension of the content.

3. Use fluency/automaticity principles to practice subskills. Although there is limited research specifically examining fluency instruction using decodable texts with younger students, incorporating fluency practice with controlled texts is a logical and aligned step within structured literacy frameworks. Practicing rereading in decodables helps build automaticity with newly learned phonics patterns while reinforcing the connection between decoding and meaning.

4. Choose appropriate text length. It is generally advised that fluency practice use passages that are approximately 200–250 words in length. This length provides enough text for students to encounter meaningful phrasing and sentence variety, while still being short enough to allow for repeated reading within a typical instructional session.

5. Choose appropriate text difficulty. Fluency instruction is typically most effective when using texts at a student’s instructional reading level, where they can decode most words accurately with minimal support. However, when the instructional focus is solely on developing prosody—such as practicing expression, phrasing, or intonation—it may be more appropriate to use texts at the student’s independent reading level to reduce cognitive load and allow full attention to be placed on oral expression.

Differentiation

- Many activities can be adjusted to be used with individual students, small groups, or as a class-wide lesson. Similarly, many linked activities can be combined concurrently to meet the varying needs in the class. For example, if the entire class needs fluency instruction, all students might participate in Choral Reading. Those who need more support with phrasing can participate using a version of the text that includes scoops placed beneath the lines to further support fluent reading.

- Many techniques used in fluency instruction may benefit English Learners beyond supporting their reading fluency. These activities can serve as an opportunity to model appropriate word pronunciations (including syllabic stress for multisyllabic words) as well as the overall intonation of English phrasing.

- If a student continues to struggle in an activity, consider adding additional scaffolds (such as Echo Reading and/or Phrased Text Reading supports), reducing the text length being read, or adjusting the text difficulty level.

- Fluency instruction techniques pair very well with comprehension-building strategies. For example, after reading a text, students can participate in paragraph shrinks, a brief retell, or a written response to what was read.

- Help increase motivation in reluctant readers by establishing a clear purpose when reading a text, especially if it will be read multiple times. This can be accomplished by setting a different goal or target for each repetition, or by bringing authenticity into repeated readings, such as rehearsing for a performance.

- For students who struggle with language comprehension, you might set a different goal to focus on with each reread to scaffold the larger goal of comprehension. In the first read, the students can focus on reading the words accurately, but subsequent reads may allow for different language goals, such as targeting challenging vocabulary and unfamiliar idioms.

- For students whose confidence is a significant barrier to participation, you might consider practicing the text with them ahead of time, so they have already gained some fluency and comfort with the passage before the rest of the class has their first run-through.

- Preview challenging vocabulary or multiple-meaning words used in new ways to help prepare students with language disorders and/or English Learners.

Armbruster, B. B., Lehr, F., & Osborn, J. (2001). Put reading first: The research building blocks for teaching children to read—Kindergarten through grade 3. U.S. Department of Education, National Institute for Literacy. https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/html/prfteachers/reading_first1.html

Cooper, S., Hebert, M., Goodrich, J. M., Leiva, S., Lin, X., Peng, P., & Nelson, J. R. (2022). Effects of automaticity training on reading performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-022-09480-7

Ehri, L. C. (1992). Reconceptualizing the development of sight word reading and its relationship to recoding. In P. B. Gough, L. C. Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisition (pp. 107–143). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Hasbrouck, J., & Glaser, D. R. (2018). Reading fluently does not mean reading fast [Literacy leadership brief No. 9436]. International Literacy Association. https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/where-we-stand/ila-reading-fluently-does-not-mean-reading-fast.pdf

Hasbrouck, J., & Glaser, D. R. (2018). Reading fluently does not mean reading fast [Literacy leadership brief No. 9436]. International Literacy Association. https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/where-we-stand/ila-reading-fluently-does-not-mean-reading-fast.pdf

Hudson, R.F., Lane, H.B., Pullen, P.C., Torgesen, J.K. (2009). The complex nature of reading fluency: A multidimensional view. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 25,4–32.

Kuhn, M. R., & Stahl, S. A. (2003). Fluency: A review of developmental and remedial practices. J_ournal of Educational Psychology, 95_(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.3

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Perfetti, C. A. (1985). Reading ability. Oxford University Press.

Rasinski, T. V. (2012). Why Reading Fluency Should Be Hot! The Reading Teacher, 65, 516-522. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01077

Rasinski, T., & Cheesman Smith, M. (2018). The Megabook of Fluency. New York: Scholastic.

Rayner, K., Foorman, B. R., Perfetti, C. A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2001). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological science, 2(2 Suppl), 31–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.00004