Assessment is a necessary part of daily classroom practice because it helps educators to better understand the needs of their students. When administering reading probes, we often use accuracy as a strong metric to guide further diagnostics and skill groupings. However, students who speak African American English (AAE) require careful analysis to yield accurate conclusions. Consider this example:

| Student reads: | Text says: |

|---|---|

| Jack he* and his sister was tease** about their name. | Jack and his sister were teased about their names. |

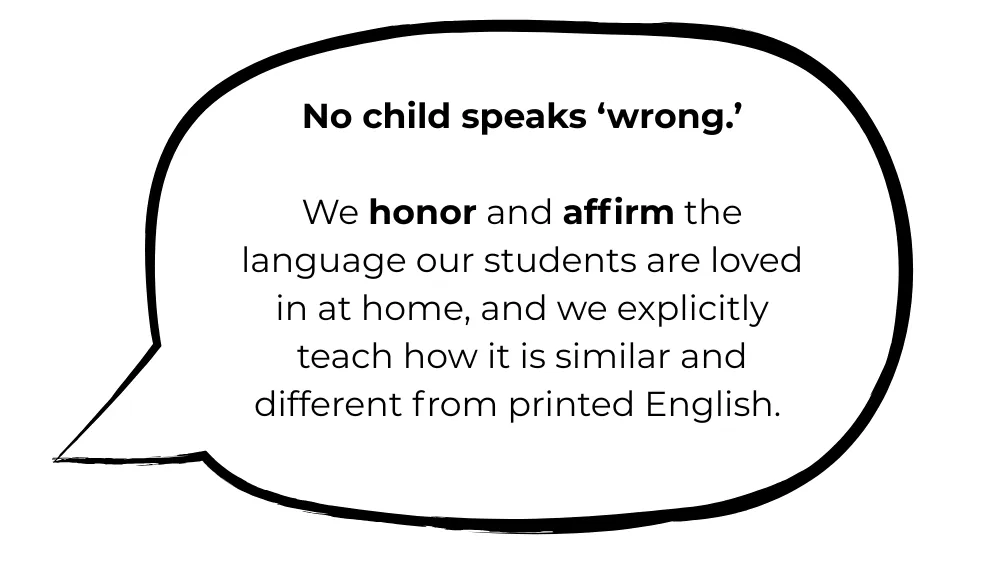

A culturally and linguistically responsive teacher recognizes that AAE has its own grammatical rules and syntax that differ from Standard American English (SAE) (the language of the text). Despite the prevalence of AAE, few educators have been taught to recognize the rule-based features of dialects, such as the syntactic features of subject expression* and subject-verb agreement (usually of was/were)** in the above example. Without this awareness, teachers may not be able to target sources of true academic difficulty versus dialectal differences. Therefore, when analyzing this Oral Reading Fluency assessment data, teachers have to be mindful that the learner reads the way they speak, so marking dialectal variations as ‘errors’ may make it seem like the student is not an accurate reader.

A culturally and linguistically responsive teacher recognizes that in AAE, the /th/ sound is represented /f/. It’s not troublesome that the learner responds in their dialect. Dr. Julie Washington explains that learners should use their dialect in oral language since it is a valid system for oral communication. However, if the teacher later sees the student spell ‘with’ as ‘wif’, then it’s an indication that they should provide instruction in the grapheme that is used in written English.

Remember, the job of teachers is not to change or correct oral language, rather to make the written language differences known to students to strengthen their academic writing.

What’s the big deal? Well, assessment drives classroom instructional decisions. The intervention or instruction that is typically given to inaccurate readers is phonics. Does the syntactic and semantic adjustments made by this bidialectal learner mean they need a phonics intervention? Of course not! But if I were strictly looking at their accuracy score, I would most likely make this incorrect conclusion. Therefore, it can be impactful to collect two different accuracy scores when working with students who speak a dialect. The first score would represent the accuracy of the passage as it is written in standard American English, while the second score recognizes and affirms the linguistic dialect of the student. Deep knowledge of the phonological and syntactical differences are required to do this work. In a 2006 study, Fogel and Ehri concluded strong instructional impacts when teaching educators the seven syntactic features of AAE. By becoming familiar with the rules of dialects, we can begin to support just instructional and assessment practices.

Let’s look at another example. This time from a phoneme segmentation fluency task:

| Student says: | Target response: |

|---|---|

| /w/ /ĭ/ /f/ - wif | /w/ /ĭ/ /th/ - with |

A culturally and linguistically responsive teacher recognizes that in AAE, the /th/ sound is represented /f/. It’s not troublesome that the learner responds in their dialect. Dr. Julie Washington explains that learners should use their dialect in oral language since it is a valid system for oral communication. However, if the teacher later sees the student spell ‘with’ as ‘wif’, then it’s an indication that they should provide instruction in the grapheme that is used in written English. Remember, the job of teachers is not to change or correct oral language, rather to make the written language differences known to students to strengthen their academic writing.

Our students are experts in the language they bring to school. Taking time to understand our learners and their language variations is our call to action. Only then can educators leverage assessment and instruction that celebrates the unique language and culture of the African American community.

- Fogel, H. & Ehri, L. C. (2006). Teaching African American forms to standard American English-speaking teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(5), 464-480.