Hi Brian,

Happy New Year! A commitment to learning more about the Science of Reading benefits not only your own professional growth, but also supports better outcomes for your students. The term Science of Reading (SOR) has become a buzzword, but that doesn’t make unpacking its meaning easy or straightforward.

As I briefly discussed in the Phonics Games column a few weeks ago, SOR refers to a comprehensive body of multidisciplinary research on literacy instruction and development. So, it’s fair to say that it can’t adequately be discussed in a couple of paragraphs. I can, however, give you a very brief overview and point you in the right direction.

The synthesis of this research is that learning how to read is not a natural process that is developed naturally with time and exposure. That is, while most children learn to speak simply by being around other speakers, they won’t best learn to read simply by being around books and being read to. Instead, children need direct, explicit instruction to connect written language to spoken language.

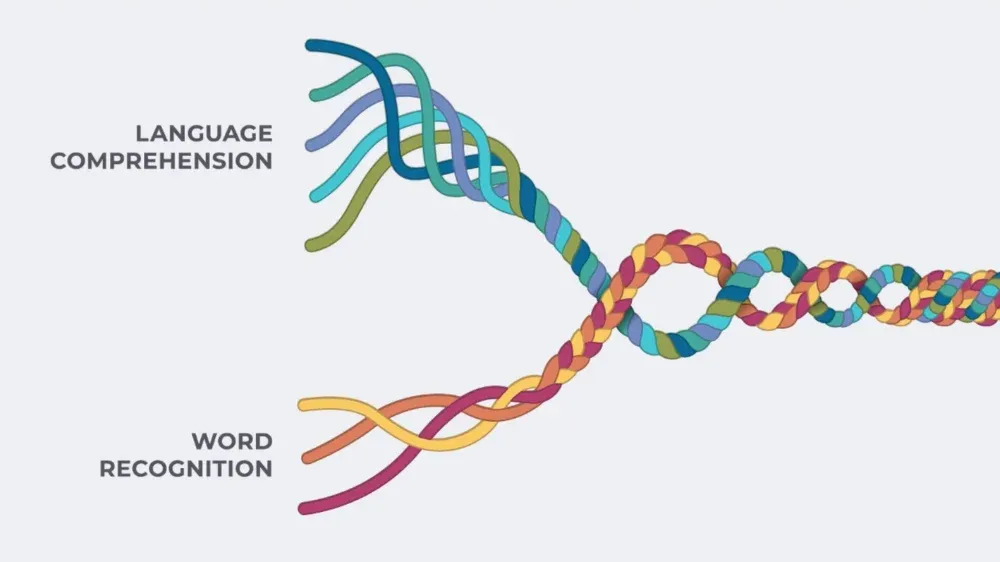

When considering how best to provide literacy instruction, educators must be familiar with the skills that go into skilled and proficient reading. Because I love a good analogy: consider for a moment a new or weak basketball player. While playing in scrimmages and games is important, this type of play alone is unlikely to develop the athlete into a strong competitor. She should also be spending ample time developing skills such as dribbling, passing, and shooting, which can advance in difficulty as she progresses. In reading, these skills are sometimes referred to as “the Big Five”: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. These five instructional focus areas were emphasized in the National Reading Panel report (NRP, 2000) and are sometimes referred to as the five pillars of reading. These instructional focus areas map onto the components of skilled reading described in the Simple View of Reading and are illustrated in more detail by Scarborough’s Reading Rope, which shows how word recognition and language comprehension develop and interact over time.

A key takeaway of SOR is that many reading difficulties can be prevented or substantially reduced when students receive early, evidence-based instruction and timely intervention. In classrooms, this means teaching foundational reading skills explicitly and early, paying attention to how students are responding, and stepping in quickly when something isn’t sticking. Instead of waiting for persistent difficulties to appear, teachers adjust instruction and provide additional support as soon as early warning signs show up.

I hope this gives you a jumping-off point to help frame deeper learning this year! Our Beginner Guides are a great place to start to learn how small shifts can better align your instruction with SOR-aligned practice, while our Skill Overviews and Lesson Toolkits can help you understand these principles on a much deeper level and help shape your teaching methods accordingly. If you’re ready to go all-in with your learning, consider one of the AIM Pathways Learning Options available through AIM Institute.

Best wishes in the new year, and please stop back and let me know if I can be of further help in your learning!